Small Press Spotlight: Stanchion

www.stanchionzine.com

Twitter: @StanchionZine

Today I am talking with Jeff Bogle, publisher of Stanchion

TG: Tell us a little about Stanchion. What do you specialize in?

S: Stanchion is two things, currently. First and foremost, it’s a quarterly literary magazine printed on beautiful uncoated paper. The magazine has a stark, black and white aesthetic and features original short stories, creative nonfiction, poetry, photography, and more. Each issue is roughly 64 pages and includes work by 20-25 talented individuals, each paid (currently $15) and who also receive a free copy of their issue. Second, Stanchion is a book press. Launched in Jan 2023 with The Woman’s Part, Stanchion Books is scheduled to publish a total of 6 chapbooks in 2023 (1 every other month) and even more in ’24.

TG: You launched Stanchion in 2020, not exactly an auspicious time. Since you've become publisher what has surprised you most about running a small press?

S: Yeah, it was a terrifying time, which is why I ended up starting Stanchion. I am a travel writer, primarily, and obviously, no one was paying for travel stories because no one could go anywhere. I was scared for health reasons and it also seemed my career was over. The anxiety over the state of the world zapped my creativity, so I remembered the joy I derived from running a record label back in the late 90s. I adored music but couldn’t play it, so I facilitated the release of other people’s art. Stanchion became a similar creative outlet. The most surprising thing about running a small press has been the indie literary community on Twitter, truly. That space has been the single most significant boost to Stanchion, in terms of being introduced to emerging writers and visual artists, as well as for selling magazine issues and books, and in general, helping me find my place in this world.

TG: Stanchion is a print journal. How have you gone about reaching an audience in an increasingly digital world?

S: Great question! It hasn’t been easy, that’s for sure! Any writer or small press will tell you that it’s a struggle every day to find new readers willing to spend a few moments with a poem or a story, let alone spend money on a physical magazine. Stanchion isn’t the cheapest thing you can read, you know? I mean, I see ads all the time to subscribe to some big names rags for like $6 or $10 a year, or something absurdly cheap like that. They are basically giving subscriptions away because they need to boost their so-called readership numbers for the sole purpose of charging more for advertisements. I’m not in that game at all. Each Stanchion costs $10, but I think that’s a good deal when you consider would-be contributors are never made to pay a fee to submit their work, no donations are ever solicited from anyone, and everyone featured inside and out of the magazine is paid for their work. My model for book publishing guarantees authors payment upfront in lieu of royalties, with more and escalating lump sum payments should the book sell well. I’m a struggling freelance writer myself, so I know how hard it is to be respected, seen, and paid. I say all this in response to your question because I think the way I try to go about running Stanchion is partially responsible for my relative success in finding an audience willing to pay for stuff in print. I’m just trying to be kind and fair to creative people, and I think that is resonating with readers and helps sell some Stanchion issues and books. But I know I will need to reach a wider audience, beyond fellow writers, to truly get these stories, poems, and books in front of the audiences they deserve.

TG: Are you open for submissions? If so, how can writers contact you?

S: Not open right now, no. I originally planned to be open all the time but that become a bit of an admin nightmare pretty quickly, as I’m a one-person operation. Magazine submission windows have been reduced down to 48 hours, 4 times a year. I do give a fair bit of heads-up, so anyone interested in Stanchion and who might consider my magazine a worthy home for their work can get some stuff together to submit. The inaugural manuscript window was about a month, last November. I’m planning on opening that window up again in late summer ’23, to round out the 2024 publication calendar for Stanchion Books. The submission page of the Stanchion website as well as Twitter and IG is where I make announcements about sub windows: https://www.stanchionzine.com/submissions. One note of interest for some (maybe) is the Anthology I’ll be publishing in early 2024 called Away From Home. With the help of editors Frances Klein and Will Klein, we are opening up that specific submission window in May. Here’s the link for that:

https://www.stanchionzine.com/post/away-from-home-anthology-call-for-submissions

TG: Is there anything else you would like readers to know about Stanchion? Any upcoming titles you're excited about?

S: I’m excited about all of the titles I am publishing haha! But the literary Gothic horror novella The House of Skin by Karina Lickorish Quinn is particularly stunning. That’s out on March 28, 2023 and is available to pre-order now. https://www.stanchionzine.com/product-page/the-house-of-skin Additionally, I started a Book Club and have a slew of goodies in store for those who plunk down a fair bit of dough to get every book I’ll publish in 2023. The response to the club has been amazing. It really makes me feel good to know there are people out there who support and believe in the work I’m doing and publishing.

Thank you so much for taking the time to chat with me. I really appreciate you.

What The Hell Am I Thinking?

Writers On Why They Write

Chelsea Stickle

It’s like I’ve been unconsciously collecting details, words, ideas. Over the summer, I visited an alpaca farm where I watched the yarn production process. At one point, you add pieces of different colored fluff to create the yarn you want. Then it all comes together and gets wound. That’s the writing process for me. My unconscious brain is always collecting things. It starts pairing different colors—different ideas with feelings—to create a thread I’m unaware of. One day I stumble onto the right container—the label, say—and boom! There’s a ball of yarn. But since I’m a writer, not a knitter, I don’t make a sweater. Instead I deconstruct the yarn. Bring it back to its original elements. Wonder at the hue, marvel at the texture, admire the animals it comes from. Imagine the sweaters that could be made. Follow where the yarn leads.

I write because this is what my brain automatically does. Because it’s fascinating to me. Because I enjoy it. That last one may surprise you. It may offend your sensibility. I know we get sold stories about suffering as art. I get it. But I’ve always felt a great satisfaction at having made something. This story didn’t exist until I wrote it. Look at the turn of phrase my brain came up with! That image! It’s a pretty great title, right? I managed to put into words something that’s been bugging me for years. Years! Isn’t that magical?

I’m done beating myself up. I did it for decades. I told myself I deserved it. Other people suggested the same. But it didn’t help me write. It didn’t make me a better writer or person. When I found flash fiction, I found a form where I could dip into worlds and disappear. Write surreal oddities with no consequences! Create a perfect moment frozen in glass. It is an immense privilege of fiction, and flash fiction in particular, to create such things. Other art forms have the same ability, but I’m not nearly proficient enough to try. One day I hope my embroidery will reach the same highs. In the meantime, I get to savor words, create scenarios and clutch my characters close.

When I’m writing—really writing and writing well—the whole world cuts out around me. I type with headphones and one song on repeat to help me stay focused and in the moment. It’s hard to express how it makes me feel alive. I feel alive when I do other activities. But with writing it’s more like thriving. Writing the thing as I mean to write it has a satisfaction that I can’t replicate another way. My entire brain is firing and working toward creating A Thing. I am creating with my whole being. Why would I ever give that up?

Over the years, I’ve considered giving up publishing or trying to get published. It’s important to keep in mind that there’s a difference between writing and publishing. One day I may give up publishing. But I could never give up writing forever. My brain wants to reassemble pieces of the world as stories. It always has. Even before I wrote, I was the girl telling campfire stories. Stories are how I understand the world. You chop it into understandable pieces and savor them.

When people ask me why I write, my quip-y answer is because it’s better than not writing. How could I drop the ball of yarn that my brain has collected and packaged for me? As long as it brings me joy and satisfaction, I will continue to write. Life is too short to cut out something beautiful and free.

Greatest Misses: Writers on Failure

On Rejections by Sara Lippmann

The first story I ever submitted to a literary magazine got picked up on its first shot.

Lola Giter tells the story of an elderly German Jewish woman in a nursing facility the night fire alarms rattle the home – and her soul. It is a story of memory, longing, and internal reckoning housed within a static frame, a cheap “Bullet in the Brain” stretched over 15 pages. My graduate program posted the open call from The Beacon Street Review (what would become Redivider), so I mailed it off, receiving the acceptance a month later in a timely, professional manner. They even invited me up to Emerson College to read at their launch party, like la-di-da.

At 25, I assumed this was the way things worked. I’d come from the world of magazines (remember magazines?!) where deadlines activated me and freelance checks sustained me (barely) and no one offered content on bowties or aphrodisiacs without a contract in hand.

Of course, I was operating under the false assumption that input equals output. Work hard, and the work will be recognized – typically, through monetary compensation. I failed to see the privilege and gross entitlement, not to mention the dangerous patriarchal misguidedness, of such a capitalistic notion.

After that first taste of beginner’s luck, rejection set in. My uninspiring crop of MFA produced stories were met with rapid “no”s or interminable silence. Sometimes, a personalized note might slip through, which I dutifully saved in an envelope for posterity as a teacher had recommended. If nothing else, I aspired to be a good student – and masochist.

As rejection slips compiled, I began to succumb to the tugs of self pity. What was I thinking? I sucked. I wallowed in my suckage. At this rate, I’d never be a writer. I should’ve considered medical school! And so on, etc.

Cue the despair, the self flagellation. Cue the comparison game, the abandoning of projects, the long stretches of not writing. Cue the brow-beating, the chest-beating, the screaming crying throwing up.

As much as rejection might have stung, all this drama was an expression of ego and self-consciousness, of fragility, anxiety, and insecurity. It was also an expression of entitlement. As if I somehow “deserved” recognition; in fact, I deserved nothing.

The artist’s life is a paradox: not for the thin skinned, and yet, a certain porousness is required to absorb the detail, emotional landscape, nuance, and gesture of the world. On the one hand, we’re told: don’t take it so personally. On the other hand, sensitivity is our superpower.

Like Lola Giter, my grandparents escaped Nazi Germany to make a safe life in New York, one rooted in the belief in upward mobility, that hard work pays off. The puritan ethic is, of course, a bill of goods. But I was spoon-fed the immigrant falsehood known as the American Dream. I’d subscribed to the tenet that success should be tangible and quantifiable.

Only this is not how the world works. There is no meritocracy. When it comes to writing, there's a chasm between art and the marketplace. Intellectually, I know this. Emotionally, it’s a different story.

The 20+ years since that first yes have been paved with near constant rejection: from lit mags, agents and editors, from residencies and grant foundations and publishers. Occasionally, there’s been a bright light.

To strive and to want, sure – this is human nature. A social-media-shy novelist sends me a note, “Is it careerist to want to be read?” Of course not. Without readers, what we have is masturbation. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that.) Readers complete the imperative. That’s the whole Forsterian gig: to “only connect.” Nor is it mercenary to want to be paid for one’s labor. As long as we’re stuck in a capitalist society, a person’s got to eat.

Reasonable goals, yet so much of this life is beyond our control. One thing we can do is stop surrendering our self-worth to the whims of submittable. Stop outsourcing our validation.

I needed to move past external judgment and take a cold hard look inside. Ask myself: what are you trying to say? Is it vital, urgent, necessary? I needed to own my voice and hone it and stop trying to conform to anyone else’s. To focus on the page, pure and simple, and to reaffirm my humble commitment to the work.

It’s difficult to write this. To show the ugly sides of myself. To admit it took until I was 45 and a global pandemic for every last patriarchal fuck to fly out the window, and to reject this wretched need for some daddy pat of approval. To learn to trust myself, for better and for worse, and to hold myself accountable.

The single worst piece of advice I ever received came from my thesis advisor, who squeezed my hand and whispered “the cream rises.” What a load of crap to serve the desperate. Talent can not only be a curse, it is largely irrelevant. All we have is our intuition, our instincts, our integrity, and our inner bullshit meter, as Steve Almond calls it. Persistence in the face of all life throws at you.

These days, I’ve become somewhat of a rejection repository. Friends, peers, students, past and present, drop me notes almost every day, often multiple times a day, reporting on agents or editors who’ve passed on materials, who’ve ghosted them. I hear them. I feel them. I’m right there with them. It’s brutal out there. I wish to hell the industry talked more about this, and the deep brokenness at the heart of the system. But most people don’t talk about failure until they’ve achieved resounding mainstream-sanctioned success, which only further mutes this aspect of the writer’s life. When the shit gets lonely, remember you are not alone. I will gladly be the dumping ground for your rejection. We can hold that space for each other. In the holding, we embrace: Everything is uncertain. There is no guarantee.

Still, we write the stories we’re driven to write.

Short Story Round Up

Five stories I’ve read this week that I really liked

Ralphie is a Good Boy by Sacha Bissonnette

The Magic Kingdom by Eliot Li

My Mother’s Sunday Lunch & Eating with my Mother in her Ovarian Cancer Kitchen by Kathryn Crowley

A Solid Contribution by Kathy Fish

Five Fat Men in a Hot Tub by Jeff Landon

Small Press Spotlight: Madhouse Press

www.madhousepress.org

Twitter: @madhouse_press

Today I am talking with Jill Mceldowney, who edits Madhouse Press along with Caroline Chavatel

TG: Tell us a little about Madhouse press. What do you specialize in?

MHP: I started Madhouse Press in the spring of 2017 while I was a grad student at New Mexico State University. I wanted to be involved in the poetry community beyond just writing my own works and having them published. I felt that it was also really important to lift up voices other than my own.

I was lucky enough to have professors who were willing to teach me how to use InDesign and to tutor me through the process of small-press publishing. New Mexico State also had a really great art studio with a letterpress. Technically, we weren’t allowed to use it so in the very early stages of the press, we used to sneak into the art department to use the letterpress—sometimes in the middle of the night—to print the covers. The covers turned out so beautifully though that it was worth it.

Madhouse specializes in one-of-a-kind, handmade, letterpress chapbooks. All of our books are edited in-house by me and my co-editor, Caroline Chavatel. We do absolutely everything by hand from the book design, cover design, printing, and binding. These books are absolutely a labor of love.

TG: Since you've become publisher what has surprised you about running a small press?

MHP: The most surprising aspect of starting the press for me was how many people trusted me with their work right off the bat. Getting started was scary and tricky because I knew the types of voices I wanted to represent but I wasn't sure if those poets would feel the same way. When we first started, I was desperate to publish Chelsea Dingman. She was basically my dream author for the press. She had just won the National Poetry Series for her first book, Thaw, and I was sure there was no way she would want to place a chapbook with us—this tiny, unproven, press with no other titles.

But she did and her chapbook “What Bodies Have I Moved” remains one of our most widely requested, and most beloved chapbooks.

The first authors who published with us, Chelsea Dingman, Emily Perez, and Joanna Valente are so talented and amazing. They really helped launch Madhouse and establish our presence. I am forever grateful to them, to the authors who have followed them, and to the authors who envision Madhouse as the future home of their work.

TG: Outside of obvious things like limited money and time, what is the biggest challenge you've faced operating a small press?

MHP: The challenges with a small press are always going to boil down to time and money. Financially we are very lucky to have been very well funded during our “start-up” years and now the press really does take care of itself as far as paying for printing, book materials, and the website. Time will always be a factor because there is only so much of it! Keeping Madhouse Press alive and well while I was in law school was especially difficult but I’m proud to say that I managed to bring out 5 titles–“Sky Raining Fists,” “Weekends of Sound,” “ Hibernation Highway,” “Shadow Box,” “Still, No Grace,”—while I was in the midst of it. That was certainly challenging but I am really proud of sticking to our publication schedule.

Another challenge is not “overdoing” it. We can only responsibly publish a certain number of chapbooks each cycle and it is really difficult to let some books go.

TG: Are you open for submissions? If so, how can writers contact you?

MHP: We currently are not open for submissions but are always accepting queries! Those interested in publishing with us are encouraged to reach out at madhousepress@gmail.com. We also welcome messages on Twitter and have connected with many authors and poets in that manner.

TG: Is there anything else you would like readers to know about fifth wheel press? Any upcoming titles you're excited about?

MHP: Our next chapbook, entitled “The Emptying Earth” by Daniel Lassell is forthcoming late this winter/early next spring!

The author of “Still, No Grace” by A. Prevett, recently won Georgia’s Author of the Year Award. Madhouse authors Taylor Byas and Luiza Flynn-Goodlett were recently named finalists for Perennial Press’ chapbook prize for their respective chapbooks; “Bloodwarm” (Variant Lit) and “The Undead” (Sixth Finch Books).

We are certainly excited about the return of the Editor’s Prize and can’t wait to read what everyone has been working on!

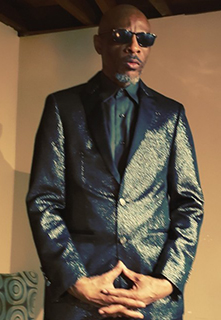

And now a word of advice from DuVay Knox

I dont BUY INTO or ACCEPT NONE of da PROBLEMS most WRITERS complain bout. All dat WRITERS BLOCK or CANT SELL BOOKS or REJECTION NARRATIVES bullshit.

The Real Problem is U gotta STOP feeling SORRY for Yo Self. And START writing wutever da Fuck U want. THEN:

Find a way 2 SELL it. And there are All KINDA ways to Slang yo shit including JEFF BEZOS real estate/Substack/Medium/Draft2Digital/Fleamarkets/ Consignment Bookstores ...its ENDLESS. Butt U prolly jes LAZY As Fuck—and:

Koncentrate too much on all da Ways U CAINT Sell!! And since U caint SELL u SOB. Butt look at it like this: as long as U SOBBING gone head n Write a SOB STORY n post dat shit on AMAZON "and" CHARGE FOR IT!! Git paid for CRYNIN Bitch!! (long as U Crying).

Im jes tryna git U 2 C a Lil Skeet Taste of Sumpen. Check me out on SUBSTACK where I talk shit n swallow spit.

Thank U Peeping this lil food 4 Thawt.

Small Press Spotlight: Fifth Wheel Press

fifthwheelpress.com

Twitter: @fifthwheelpress

Today I’m talking with nat raum, publisher of fifth wheel press

TG: Tell us a little about fifth wheel press. What do you specialize in?

fwp: We're an independent publisher of queer writing and art. We began as a photobook press for lens-based artists of marginalized gender identities in 2019 to fill a gap in a publishing world dominated mostly by cishet white men. We expanded to begin publishing literature in 2021 and chose to shift our publishing focus to the queer community at that time as well. Now, we publish chapbooks, anthologies, and both solo and group photozines. We also maintain a blog that regularly features queer creatives in the form of reviews, interviews, features, and critical essays.

TG: Since you've become publisher what has surprised you about running a small press?

fwp: I think I speak for a lot of press owners when I say that I didn’t have an idea of the true scope of work involved in owning a press. Being a sole owner with a few part-time editors helping me means that I wear a lot of hats, and I’ve learned that I’m definitely better at some things than others. So I guess to answer the question more directly, I don’t think I envisioned juggling this many things at once.

TG: Outside of obvious things like limited money and time, what is the biggest challenge you've faced operating a small press?

fwp: I think I tend to be more ambitious than time will allow me. I know that still relates to time, but it’s definitely also the specific problem of biting off more than I can reasonably chew in a given amount of time. While I don’t regret anything, I definitely think there are things I’d do differently planning-wise if I’d known how difficult it would be to juggle the logistics of so many publications at once. We had a big 2022! But I’m also a grad student with a job, so I’m hoping to strike a better balance with 2023.

TG: Are you open for submissions? If so, how can writers contact you?

fwp: We just finished our open call for manuscripts, and we don’t have an anthology call open at the minute, but we’re opening submissions for early 2023 features and critical essays on our blog on 11/1. They’ll be reviewed on a rolling basis until we fill up the first three months of the year. We’d like to emphasize that these are also open to visual artists and writers working in hybrid/visual media!

TG: Is there anything else you would like readers to know about fifth wheel press? Any upcoming titles you're excited about?

fwp: We offer a subscription for our chapbooks that’s a great way to read our titles at a substantial discount! Other than that, we absolutely recommend picking up a chapbook of ours, even and especially if you don’t usually consider yourself a poetry reader. I look for really unique and compelling manuscripts, and I think there’s so much to love in every book we publish (not to sound biased or anything). I also would be remiss if I didn’t draw attention to our photography monograph series, as I really consider that our “roots” and am extremely proud of those books.

What The Hell Am I Thinking?

Writers On Why They Write

Sucky Writer

by Paul Hostovsky

I write every day. Not because I’m disciplined. I’m not disciplined. I’m addicted. Addicted to writing. Writing feels good, so I do it. A lot. “If it feels good do it,” we said in the sixties. Actually, I didn’t say that in the sixties. I was still sucking my thumb in the sixties. Which felt good. So I did it. A lot.

As a writer, I suspect that I suck. I have suspected it all this time (while pretending to myself I am great). I think it’s because I sucked my thumb until I was thirteen and a half. Secretly, shamefully, inexorably. I don’t remember how it started and I don’t remember how it ended. It’s possible that it never ended but just morphed into other addictions. Like writing. “We give up our addictions in the order they’re killing us,” says my sponsor, Phil. “Or else we just keep substituting one for another, and they kill us cumulatively.” I should tell you that it was the right thumb, never the left. I tried the left, of course, but it didn’t satisfy the way the right one did. This greatly puzzled me, and I remember holding both thumbs up, one next to the other, to see if there was some anatomical difference of shape or size or curvature that I could detect, something that would explain why the right one was the go-to thumb and the left one just didn’t do it for me. They were mirror images, as far as I could tell. They were like identical twins whom no one could tell apart, and the only reason I could tell them apart was because I had fallen in love with one of them.

As for the writing, that addiction didn’t start until later. Quite a bit later. After the thumb, or maybe contemporaneous with it, was kissing the cat on the mouth, which deeply repulsed my mother. “DON’T kiss him on the mouth, for God’s sake, you have no idea all the germs percolating inside the mouth of that cat. If you have to kiss him, kiss him on the forehead.” A chaste kiss on the forehead she could abide, but the thing was, he didn’t really have a forehead. He had a roundish little noggin with a triangular nose and two periscopic ears that had a way of changing shape like a hat changing heads on his head whenever I kissed him unrestrainedly on his oh-so-kissable mouth, his eyes dilating like the binocular view from space of a world going up in smoke.

There were, of course, other addictions. There was masturbation, which I thought I had invented. It was the only manual activity I could perform dexterously with my left hand. In fact, I still favor the left. But in everything else I am right-handed: throwing a ball, sucking my thumb, writing sucky poems. I have no memory of sucking my thumb while simultaneously touching myself down there, but the evidence, i.e. the proficiency of my non-dominant hand in that department, seems to point to such a picture.

I think of King David lying supine in the royal bed, fantasizing about the dark-haired Bathsheba, the royal cock stiffening in the palm of the psalmist as his mouth begins to open with song. Of course, it’s hard to sing when you have your right thumb installed in your mouth. Which makes me think I must have shed the thumb finally when I picked up the pen, and started writing those plaintive love songs to Abigail Plotnik in the 7th grade. In fact, writing is just about the only addiction I indulge in these days, having given up almost all the others in the order they were killing me. I’ll probably never give up writing, though. And if my writing mostly sucks, well, I chalk that up to the iterative evolution of the thumb.

Greatest Misses: Writers on Failure

MY SPARKLING DEBUT AS A NOVEL WRITER Or, How I Woke Up and Smelled the Coffee By Jenna Junior

It’s a story a lot of people will have in common with me. Quarantine hit, the pandemic was raging with no answers or solutions in sight, and people across the world were getting the opportunity that had always seemed impossible: they finally had enough time to do whatever it was they had been putting off for years, decades even. This was the golden age of the sourdough starters, tufted rug weavers, candle makers, frou-frou coffee drinkers. This was the closest we would ever be to the frame of mind our mothers had in home-ec class. For me, it was time to sit my ass down, stop making excuses, and finally write my novel.

I’ve always considered myself to be a novel person whose work life forced me to settle for being a short story writer. I felt there was something substantial in me that could be coaxed out if only I had a Stephen King-like setup: an office to work in, an animal sitting in my lap, a partner who could entertain themselves for five hours a day, and maybe a growing drinking problem. The summer of 2020 gave me all these things in abundance. It also seemed bizarre good luck that I got furloughed from my job with a surprisingly better paying gig at unemployment. In my mind, I was now being paid to write at last. Not only that but I was being paid way, way more to write at home, unemployed, than at my job where I teach people to write 8 hours a day. Go figure.

It was truly an idyllic time for me. I would wake up, attempt to do yoga for the first time in my life, pour a cup of coffee that cost me far less than the pretentious things I drank pre-pandemic, throw on a cardigan I didn’t need in the Oklahoma summer, and just sit and write. I found myself often swaying, as if I was a piano player swept up in the music my hands were coaxing into existence. I rocked like a woman possessed, eyes fluttering, mumbling to myself. When I finished, I had the slick sheen lovers often acquire after the deed, and the heartbeat to match. If I smoked still, I would be lighting up the minute I finished my ten-page quota. I would’ve really had a problem, though, since I ended up writing 180 pages in two months.

I was feeling great about my process. I felt I was plunging into the depths of my soul, grasping at handfuls of literary pearls and resurfacing as a better, stronger writer than ever before. I joined a writer’s group via Zoom, connecting with people all over the country, who unfortunately had no interest in reading my horror novel and preferred to show new poems about their stressful years as ballet dancers, high school outcasts, and jilted lovers. I didn’t care, though, because I felt I had a little secret. They were all amateurs—something I realize all writers believe, with various levels of trying to still appear polite to others. I was writing a novel, so clearly I was just there to be supportive and did not need support myself.

After finally printing out a good chunk of my book so I could feel its satisfying heft at its halfway mark, I decided to let my partner read it. I am like many wrongfully confident writers in the sense that I hand off my work for criticism when really, deep in my gut, I feel assured the only thing that will come back my way is adoring praise. Still, my partner is also a fellow writer who was good enough to meet Neil Gaiman after winning a literary prize, so I allow him entrance into the sensitive spot my brain reserves for accepting feedback. I left him with the manuscript, thinking I may have some minor reworking ahead, and went on my merry way to finish the damn thing.

Days had passed with no word. At first, I passed it off as him being too busy to take the time to get to it. Then I realized we were trapped in our apartment with no friends to come calling, no events to attend, and no real responsibilities besides feeding ourselves and our cats. The silence expanded, and the cold touch of realization gripped my heart. There was a reason he wasn’t speaking. Finally, I confronted him as he was in the bath with my manuscript clutched in his bubble-soaked hands.

“What do you think?” I asked.

“It’s…fun.”

“Fun?”

“Yeah, I can tell you’re having a good time writing it.”

These are the words you tell a child when they draw a picture of something that looks like shit, or when they do a cartwheel that’s closer to an elaborate fall to the ground. I am a published author. I have done readings. I teach college students what to do and not do based on my own validated skills as a writer. I do not write for a good time. I write because that’s the only thing I am good at.

Wordlessly, I retrieved the manuscript to examine it under this new, harsh light. Surely he was wrong. Surely I have misjudged his critical thinking, taste level, and overall intelligence.

No.

He was most definitely right.

What lay before me was a stream of consciousness that read more like a teenager’s LiveJournal than artfully crafted horror literature. Me, the harshest critic Goodreads has ever known, now must swallow my bitter reviews and scoffing to accept that I had written a goddamn hot mess of a book with no character development, no direction, and certainly nothing worth even salvaging. This was a steaming pile of shit, created by my own two hands. The scenes that I thought would make people’s skin crawl made my eyes roll. The characters I thought people would love were really just every annoying person I’ve ever met put to paper. The plot was silly string, sprayed out by a manic chimpanzee, with no rhyme or reason behind its stream.

The next morning, I awoke, began my routine of performing an awkward downward dog, filled my mug with lukewarm coffee, shrugged into my thrift store cardigan, and began to live my new life as a humble, meek, and mildly talented short story writer.

Small Press Spotlight: Unsolicited Press

Unsolicitedpress.com

Twitter: @unsolicitedp

Instagram: @unsolicitedp

Today I’m talking with Summer, Publisher and Managing Editor of Unsolicited Press.

TG: Tell us a little about Unsolicited Press. What do you specialize in?

UP: Unsolicited Press is based out of Portland, Oregon and focuses on the works of the unsung and underrepresented. As a womxn-owned, all-volunteer small publisher that doesn't worry about profits as much as championing exceptional literature, we have the privilege of partnering with authors skirting the fringes of the lit world. We've worked with emerging and award-winning authors such as Shann Ray, Amy Shimshon-Santo, Brook Bhagat, Kris Amos, and John W. Bateman.

TG: Since you've become publisher what has surprised you about running a small press?

UP: The biggest surprise is learning that the publisher and the author are the ones who do the most work, and yet are the ones who receive the least amount of money from the sale of a book. The retailers and distributors and wholesalers skim so much off the top, we get somewhere between $2-3 per book depending on its page count.

TG: Outside of obvious things like limited money and time, what is the biggest challenge you've faced operating a small press?

UP: The biggest surprise is learning that the publisher and the author are the ones who do the most work, and yet are the ones who receive the least amount of money from the sale of a book. The retailers and distributors and wholesalers skim so much off the top, we get somewhere between $2-3 per book depending on its page count.

TG: Are you open for submissions? If so, how can writers contact you?

UP: Yes. Here: https://www.unsolicitedpress.com/guidelines.html

TG: Is there anything else you would like readers to know about Unsolicited Press? Any upcoming titles you're excited about?

UP: Oh god, I mean we are over the moon about every book we release. We just put out a choose-your-own adventure memoir by Jackson Bliss. All I can say is this guy is the real deal. He matters and his work is powerful.

A Growlery Update, or What I Did on My Summer Vacation

It’s been the question of the summer, the cause of all the uncertainty keeping us up at night, the source of that ever-present apprehension in our guts: When will The Growlery post new content? And the answer is: Well, right now, I guess. We were on summer hiatus, which is a fancy way of saying I needed a break. Anyway, we’re back!

During the down time I’ve been working my way through Underworld by Don Delillo. The novel was on my to-read list for years, but I’d avoided it mainly due to its size—827 pages—and also its reputation as a Big Book, a magnum opus, an amazing literary mirror reflecting a metastasizing society back at itself. And, honestly, it’s all those things, just unabashed maximalist fiction. It’s great. I fucking love it. I know the novel has its naysayers who think it’s too long, too digressive, has too many tangents, or is otherwise incoherent, and I think that much of the criticism, like everything else, comes down to personal preference. Which is fine, of course, enjoy what you want and piss on the rest, the earth is boiling and there are worse fates headed our way than having to sing the universal praises of a twenty-five-year-old novel. However, there is one aspect of Underworld in which I will hear no dissent, and that is the prose. This book is relentlessly well written, almost impossibly so. You know how when you’re reading, and you notice the author really going for it and the writing jumps to another level for a paragraph or a few pages or an entire chapter? Well Underworld is written almost entirely in that hyperdrive state. The emphasis Delillo puts on sentences in a book this size is really hard to believe.

The other thing this novel has me thinking about is the topics writers choose to write about, the scenarios and premises and types of characters that we are drawn to again and again. I know it’s a question writers hate—Where do you get your ideas?—but why do some of us focus on families or childhood or love affairs or death or the pivotal events that shape human history? Why do some writers create worlds in the deepest parts of the universe while others are obsessed with the towns they grew up in? Why are some of us attracted to life-and-death situations and others invested just as deeply in the small, hard to define moments that make up a small, hard to define life? Underworld is a novel that is literally about the whole second half of the 20th century and I can’t grasp the ambition and ego it must take to try something like that, to wake up and say, “I’m going to write about baseball and nuclear proliferation and war and sex and love and race and class and art and movies and graffiti and music and waste containment and the desert and, for good measure, I’m going to make J. Edgar Hoover a character. I’m going to make Jackie Gleason puke on Frank Sinatra’s shoes, baby!”

Anyway, it’s the best book I’ve read in quite a while and if you haven’t checked it out, it’s worth taking the trip.

So, how was your summer?

–Aaron

The Workshop Experience

Workshop with a Future Nobel Laureate by Jon Fain

One of the fiction writing workshops I took way back when was with Isaac Bashevis Singer. He had just won the National Book Award for his short story collection, “A Crown of Feathers.” He would receive the Nobel Prize for Literature a few years later.

I went to Bard College for multiple reasons: its small size, beautiful campus on the Hudson River, three-to-one female-to-male student ratio, and because it had a history of having well-known writers on its faculty, such as Saul Bellow, Ralph Ellison and Mary McCarthy. They also brought in “Distinguished Visiting Professors” like Singer each year.

Mr. Singer, at the time in his early seventies, was bald and bright-blue-eyed, dressed usually in a light gray suit. He travelled the 100 miles back and forth from New York City to Bard with a young woman assistant. Besides those of us who were writing majors, there were students across academic disciplines signed up for his workshop. It was a large class because of that. Some students always set up cassette tape recorders to record the sessions.

It was clear the workshop would lack even the modest rigor of the one I’d previously taken, the semester before. At the start of each class, Singer would ask who had a story. Students would read their work, as opposed to him reading it, or copies being distributed to everyone before class. Singer commented first about what he liked, sometimes asking questions. The rest of us would weigh in, and as I found to be the case throughout all the writing workshops I took, some students would always echo the professor’s comments with theirs.

One time I responded to a story saying that I thought there were a too many contemporary references; I found the brand and celebrity names distracting, thought it was a lazy way to root the story in a particular time period. Singer dismissed my concerns with a smile, saying that there could be footnotes of explanation for readers in the future.

Multiple students brought in stories that seemed written to appeal specifically to him, Jewish family sagas. One had sisters vying for the attention of the same man; another told about a matchmaker at odds with a spirit—a dybbuk, one of Singer’s frequent devices. Near the end of the semester his personal assistant read something, presented as her first attempt at fiction. Like those others, its subject matter was in the mode of what Singer wrote; perhaps an homage, an imitation, or both.

Other students who’d been in the previous workshop with me read stories that they’d presented at that class rather than new work, and when it was my turn, I did the same. The main character is a bar bouncer in a California coastal town between Los Angeles and San Francisco, and as it opens, he breaks up a fight. Another customer at the bar approaches him and says how he’s looking for someone who can handle tough situations, and offers the main character a job. Curious, and interested primarily because it will be a large jump in pay, the bouncer agrees to go with the man and check it out.

They leave the bar that night and drive up the Pacific Coast, to a large mansion. Once inside, it’s revealed that it’s a home for deformed children, an orphanage of sorts, supported by a mysterious rich man, a Mr. Astor. Over the coming days, the ex-bouncer learns he’s been hired to protect the mansion against some locals who have found out about its occupants and want to shut it down. He meets Mr. Astor, other staff, and the children, particularly struck by the two oldest, both teenagers—a boy “with a face like a dog,” and a “beautiful girl born without arms.”

It doesn’t take the main character long to become infatuated with the girl and to clash with the dog-faced boy, who is an unruly handful. At the climax, the main character discovers them naked in bed together. Enraged, he pulls the boy off the girl and begins beating him. Other staff intervene, and it’s revealed that the boy is Mr. Astor’s son, and he’s set this home up for him so he’d have friends. The main character, with a mix of confused emotions, takes off into the night.

After I finished reading the story, there was a moment before Singer said, “So… this is a true story? It really happened?”

I laughed, surprised. “No, I made it up.”

He didn’t believe it, for some reason. At one point in our back and forth, I admitted that I’d given the boy the name Jo-Jo, after the famous carnival freak, “Jo-Jo the Dog-Faced Boy” and that only seemed to confirm Singer’s suspicions. But I kept insisting the story itself wasn’t true.

Finally, Singer said it didn’t matter. The subject was “not appropriate” for fiction. It was “too horrifying,” he said.

I didn’t know what to say to that. As usual, the students who always agreed with Singer piped up in support.

Half the class or so however disagreed. One of the students said how she’d always thought if a story sounded real, it was a mark of a well-written story. I thought that too, that the best fiction created a believable world, the old “suspension of disbelief.” If I could bring everyone along with something this outrageous, I was doing something right.

The class moved on. The next story was from another student who’d been in the previous year’s workshop. “Puppy Palace” was a long one, twenty pages that seemed longer, about a young guy working in his family’s pet store. It was a fucking dog, but Isaac Bashevis Singer liked “Puppy Palace” quite a bit.

A few years later, after he won his Nobel Prize, either in his speech, or in some interview, Singer was quoted as saying Henry Miller should have won it.

I agreed with him finally about something, at least.

The Workshop Experience

Gladiator by Dia VanGunten

Not far from Lake Erie, like a suburb of Detroit, there’s Toledo, a city so alluring that Jamie Farr was willing to crossdress if it meant the military might ship him home. Or so he claimed. Toledo was just an excuse for Klinger to indulge a love of silky nighties. I got that much but I couldn’t grasp how a soldier longs for home. I caught M*A*S*H on syndication, on a Toledo station, when I still wore purple kangaroo sneakers. I didn’t see the joke in Jamie Farr’s exaggerated reverie. He’d blink glittery eyes and fluff his feather boa. Oh, if only I could go back to Toledo and eat one more Tony Packo's hotdog.

I was perplexed: “Why does he like hotdogs so much? What’s so special about Toledo?”

Dad said it was funny because even Toledo is better than comin’ home in a body bag.

I figured me and Max Klinger may share a love of turbans but I wasn’t gonna miss our hometown. I left and had loads of fun in the Austin punk scene with my punk-rock crowd...thus answering my childhood question: What makes Toledo special? There are not enough punks for a punk scene. Punks gotta hang with the ska guys who go to the poetry open mics at the sub shop just to crush on the college coed who sneaks a cigarette with a 90 y.o. poet. That guy works at Jeep but plays drums at a jazz club where all the starving artists gather because there’s a one dollar spaghetti special on Sunday nights.

Naturally, an elderly nun enrolled in the University of Toledo. She submitted a shit poem to a poetry workshop. Just one glancing nudge from Prof and I was happy to fill the uncomfortable silence.

“With all due respect, I don’t give a shit about Angela and David’s holy nuptials and their union before god. Furthermore, I don’t think you do either.”

“I’ve lived in a convent for 45 years. My life isn’t exactly exciting. Not like yours.”

The class snickered because we’d just finished with my latest. It began with the line: “If I was Gustav Klimt’s girlfriend, there’d be the issue of jealousy.” It ended with a blow job. Sister was more distressed by the laughter than I was. She leapt to my defense.

“No, no, I didn't mean...I love your poems. But I don’t have that kinda life. I’m boring.”

“You haven’t lived your life then? You’re not a person?”

“No, I am. I ammmmm.”

She turned to the class, her m’s emphatic.

“Tell us about this convent. Cuz we all know I’m no nun. I’d like to know what it’s like!”

The professor dispatched us into the sunshine. Spring was exploding on campus. Apocalyptic joy broke out among the midwestern mole people. It was the 90’s so obviously I was wearing platform heels and a baby doll dress. Paul said I looked good for a girl who was most certainly going to hell.

“You’re so fuckin’ shameless.”

He smiled and ogled my bare knees; half letch, half catholic boy scared that hell might be catching.

“Be nice to the old lady in the habit, Dia. Why can’t you just tell her the poem is good?”

“Because it wasn’t.”

Everything is so obvious to an autistic. It felt more disrespectful to lie to a fellow writer who was trying to hone her craft. I wasn’t gonna waste her academic investment with obligatory niceties normally afforded to someone of her age and status. We were a writing workshop in a working class town, on an egalitarian campus cradled by factories. I was ribbed for running the nun outta school but our classmates

underestimated her. She showed up the next week with a poem about the convent’s computer lab. There

were only 6 computers and the sisters fought like gladiators to get online.

At semester’s end, she slipped me a note. Thank you for treating me like a writer. You helped me find my voice. A few months later I got another envelope with a check. My poem about Gustav Klimt was the first prize winner. The contest was legit but I didn’t enter it. It wasn’t me who devised that one brilliant edit.

I didn’t select Times Roman and type it up on a computer.

![]()

Small Press Spotlight: Tough: Crime Stories

http://www.toughcrime.com/

Twitter: @tough_crime

Today we are talking with Rusty Barnes, of Tough.

TG: Tell us a little about Tough. What do you specialize in?

Tough: Tough is an online journal of crime fiction and occasional reviews printing on the first three Mondays of the month. We began by looking exclusively for rural-based stories, and as fiction editor Tim Hennessy took on a formal role and the to-read pile became repetitive, we cast a wider net. We are only slightly biased toward the rural and hard-boiled, though I’m pleased to say that we hope our look this year is going to be much different, as we have opened our minds to the wonders of the crime fiction world that do not involve rabid and man-hunting squirrels or mountain men heaving their beer cans out the truck window and into the ditch while driving home to the little woman.

In short, we’re open to a wider sense of story than our submitters, and our publishing history, would indicate. Traditional mysteries, amateur detective and PI stories. Police procedurals and police detective stories, as well as the gamut of the other side of the law: gangster stories, criminal protagonists, and the like. I find myself also drawn to cozies recently. I admit this is my current editorial bias. I would have never guessed I’d be interested in cozies even five years ago. Here we are, though, in the 21st century and the world going to hell in a hand basket, as my late dad might have said. And I was so much younger than. I’m older than that now. I enjoy a spot or two of redemption where it’s due, and bad guys getting it in the gut sometimes is just what needs to happen in a story.

We don’t specialize per se. All of the people who read for us—Tim Hennessy, Tough fiction editor, and editor of Milwaukee Noir, Ted Flanagan, managing editor and author of Every Hidden Thing, Rider Barnes, reader extraordinaire (also my son), and Nikki Dolson, editorial pinch-hitter and also the author of All Things Violent and the collection Love and Other Criminal Behavior—read widely and want to see variety.

TG: What kind of stories stand out to you or make an impression when reading submissions?

Tough: What impresses me most is a story with a strong through-line. Stories we get are often good, even excellent examples of prose that fall short in keeping things moving during the meandering middles of their stories. Many writers like to pay lip service to plot, preferring, I guess, to dazzle with their prose than provide a story that hits all the Save the Cat beats. There’s a reason that book is so popular. Contemporary writers, unless terribly gifted or incredibly well-read, need it.

TG: You were a co-founder of the great lit journal Night Train. How has your experience with Tough compared?

Tough: Tough is a completely different animal than NT. Night Train was a 501c3 corporation with all the duties and costs associated, and it ended in 2016 because I was tired of chasing after money. It cost thousands of dollars to operate. Tough exists because I caught a wild hair in 2017 and missed editing formally, shepherding other writers to publishing. Unless I’m doing a print issue, it costs me only $150 out of my pocket each month. What might otherwise be my mad money is instead paid to writers whose work I love enough to invest that cheesesteak-and-beer money.

TG: Outside of obvious things like limited money and time, what is the biggest challenge you’ve faced operating a small press?

Tough: Challenges include getting the journal to be known. We’ve had some successes getting our authors noticed, though that has more to do with their quality than our efforts. We nominate for all the awards we know of, Anthony awards, Derringers, and soon hopefully, Edgars. It’s nice being a sort of stepping stone to the big leagues that pay decently. Our payment is token only. We’ll never be able to offer to pay Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine or Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine money, so I’m content as a sort of minor league journal with big league aspirations and hobbyist money. Having said that, S.A. Cosby won an Anthony with a Tough story, Kristen Lepionka appeared in Best American Mystery and Suspense, and Matthew Lyons appeared in Best American Short Stories edited by Roxane Gay.

Another challenge is getting to know the market as an editor. I’ve spent my time since my first novel came out in 2013 reading crime fiction in a frenzy. My first novel, Reckoning, gave me an intro to the crime fiction scene through the efforts and friendship offered me by Jedidiah Ayres, Brian Lindenmuth and Anthony Neil Smith, among others. My Kindle is filled with classics of the genre and some names that would probably be new to you even with a ton of experience in the field. I keep my ear to the ground and my heart open to new things. Hence my current interest in cozies.

TG: Are you open for submissions? If so, how can writers contact you?

Tough: We are open for submissions at redneckpress.submittable.com and for questions via email at toughcrime@gmail.com or via Twitter @Tough_Crime.

TG: Is there anything else you would like readers to know about Tough? Any upcoming titles you're excited about?

Tough: TOUGH: Tough wants your attention. We have published many names that were previously or are now recognizable names, but our interest is piqued doubly when the author or submitter is unknown to us. Please give us a shot. We accept maybe 1 in 12 stories submitted, so the odds are long, but we remember details and submitters even if we don’t explicitly say so. We’ve accepted debut stories, and stories by people with hundreds, even thousands of published stories under their belt, so it may not be the first story you send that works for us, but the second or third might. We see many stories that are pastiche. The crime genre has a rich history, your favorite writers possibly are our favorite too. That said, we want a story only you can tell. We love stories that use elements of the genre but have a fresh perspective or approach to the familiar elements we all love.

What The Hell Am I Thinking?

Writers On Why They Write

How Writing Saved My Ass

by K.B. Jensen

One of my early journals has ridiculous drawings, and the words in crooked kid handwriting: “No one understands me.” Why I write has shifted wildly many times between understanding, joy, escape, survival, recovery, and exploration. But in the beginning, writing was a way to be understood and understand myself. Who the hell am I?

I’m a writer who flunked first grade. I often couldn’t hear the teacher. My classmates told me, “you should have been listening” when I asked what Mrs. Nielson said, so I stopped asking. I also turned a standardized test into a game, and was the kid who tried to memorize the alphabet backwards instead of forwards. My hearing was eventually fixed with ear tube surgery, but the experience left a few marks. I felt like my writing showed people I wasn’t dumb. My stories were one reason I was put in the gifted program in third grade. Then I had to prove I belonged there. I became a perfectionist and a straight A student.

Over the years, multiple people told me, “you write beautifully,” but I hated that because what did it actually mean? As I got older, I became terrified about showing others my writing. I mainly wrote for myself. I took creative writing classes in high school at the University of Minnesota, and I loved it. But there was always this fear. What if other people read my writing and think I’m crazy?

I went to the University of Wisconsin-Madison and became a journalist. I loved it. When my stories appeared in front of 100,000 subscribers, I thought, maybe this will finally help me get more okay with people reading my fiction. It didn’t, because even though I was writing stories, they weren’t really my stories. They belonged to other people’s lives. I was particularly good at covering crime, because I cared about the victims’ families, but it took a toll on me emotionally. When my husband I were expecting our kid, I knew I’d never be able to pick my daughter up from daycare on time if I stayed covering murders. I knew from experience that if a body was found in a forest preserve, for example, I’d be looking at a twelve-hour day talking to sources and covering developments.

So I became a stay-at-home mom and I turned to my own writing during my kid’s naptime. I’d type as fast as I could because I never knew when my baby would wake up. I wrote my first book, Painting with Fire, a crime novel, that way, and it was cathartic, but when it came to publish it, I was still afraid. What if they think I’m crazy?

Then life got really isolating, and I wrote for survival. My husband was traveling a lot for work, worked full time and went to grad school in the evenings. Our families didn’t live nearby. I spent a lot of time alone with my baby and was put on an antidepressant medication for neck pain from a car accident. It triggered a breakdown. My husband went on a business trip and when he came back I was yelling and not coherently. I had been able to take care of my kid like a reflex, but I hadn’t been able to take care of myself. I forgot to eat, shower and couldn’t physically sleep for four days. I wrote almost constantly, especially at night.

While he was gone, writing became a way to escape and cope with the world and avoid suicide. I typed tens of thousands of words. At that time, writing was a life raft. Writing kept me from taking all the pills in the cupboard. I remember writing at night, “I sound manic.” Writing what I called a long Minnesotan goodbye. It felt like drowning. I couldn’t stay lucid long enough to come up and ask for help. I was trying desperately to remember all the people I loved, to stick around.

My husband took me to the ER, and I was hospitalized. I insisted on keeping my pen despite protests from the hospital staff. “Take away my pen, you take away my life,” I said. “It’s how I make sense of the world.” It sounded dramatic, but it was the truth. Thankfully, they let me keep it.

My husband came to see me every day during visiting hours and I wore his T-shirts in the hospital because I missed him and they smelled like him. I realize I could write a whole memoir about this, but long story short, I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, prescribed medication and therapy, and spent the next years using my writing to recover. I could see my moods on paper, in my stories and poems. I used my writing as an early detection alarm system. I no longer worried as much about people thinking I was crazy, because I was a little crazy.

I eventually became so ridiculously stable and seemingly even-keeled, that most people who’ve met me since have no idea this ever happened unless I tell them and it’s always a surprise. Ten years have gone by since the manic episode. I’ve published books and won awards, and built a career in publishing. I write for different reasons now. But it’s still not for money and not for fame.

I still sometimes use writing as gauge, a way to assess my mood. Am I down? But more often, I write out of joy, the fun and adventure and exploration of it. I still like the idea of being understood, the idea of others feeling the things I feel, of creating art that makes people think and feel empathy.

I don’t write for the same reasons I used to. It’s not because I have to. It’s not a matter of life or death or feeling misunderstood. I write because I love writing. Because I’m a writer. Because it’s what I am and what I do.

Small Press Spotlight: Cowboy Jamboree

http://www.cowboyjamboreemagazine.com/

Twitter: @CowboyJamboree

Today we are talking with Adam Van Winkle, of Cowboy Jamboree.

TG: Tell us a little about Cowboy Jamboree. What do you specialize in?

CJ: We want Mystic, Georgia and Thalia, Texas and Billy Ray's Farm and Dream of Pines, Louisiana and American Salvage. We want stories and song and verse and essays with place and character so deep we can smell 'em, so well told that we see how they exist before we met 'em and see how their lives play out once we leave 'em. We want good grit lit. This is what we seek and what we publish.

We are not—I feel compelled to say—in search of gunslingin, over-machismoed, historically (exhaustingly) detailed western stories. These get submitted to us all the time. While we like the nontraditional westerns of say Cormac McCarthy (see Blood Meridian or All the Pretty Horses) and a lot of contemporary westerns (Justified was a great television version), we are not a western rag. We'd love a story or essay on the fallacies of the myth of the west in a contemporary setting (see Sam Shepard's True West). Our Cowboy Jamboree name refers more to our love of old Country music--Hank Williams and Townes van Zandt and Johnny Cash and Patsy Cline. Check out the soundtrack for the film version of The Last Picture Show and you'll get it.

TG: Since you've become publisher what has surprised you about running a small press?

CJ: The most surprising thing has been the loyalty, if that's the right word, of authors. The fact that so many folks that have published in CJ Magazine or in book form with CJ Press return to try to do it again makes me feel good about the support they get and the satisfaction with the process and publication. It makes me feel like we're doing something right around here.

TG: Outside of obvious things like limited money and time, what is the biggest challenge you've faced operating a small press?

CJ: Certainly time. Reading magazine and manuscript submissions takes a lot. Fortunately, CJ has developed clear tastes and style, and I can tell pretty quickly if it's what we want or not.

TG: Are you open for submissions? If so, how can writers contact you?

CJ: I'm just not into Submittable. We take submissions at cowboyjamboree@gmail.com. We are currently accepting subs for our upcoming fall issue, the Larry McMurtry inspired, incited, influenced "THALIA ET ALIA." We also have two anthologies open for submissions for the next month or so, one inspired by HANK WILLIAMS, the other by BOB DYLAN. See cowboyjamboreemagazine.com for more details. If you want to publish a book-length work with CJ Press you have to have previously published in the online magazine or another CJ project.

TG: Is there anything else you would like readers to know about Cowboy Jamboree? Any upcoming titles you're excited about?

CJ: Anything Sheldon Lee Compton does is magic. We're lucky to be the exclusive home of his fiction and now, after publishing his memoir on his life as it relates to the life and death of Breece D'J Pancake called THE ORCHARD IS FULL OF SOUND, his nonfiction. Check out our SLC page to see new stories and other snippets of upcoming SLC projects: cowboyjamboreemagazine.com. FYI: he's got a detective novel in the works that may get some serial previews there . . . I'm proud of everything we do, but I'll also make mention of a few upcoming titles. Benjamin Drevlow has already put out two books with us and we are publishing his upcoming THE BOOK OF RUSTY, tracing the life of an alter-ego of Drevlow. His previous, INA-BABY, A LOVE STORY IN REVERSE and A GOOD RAM IS HARD TO FIND were brilliant. Daren Dean is also going to make it 3 releases with CJ with his novel ROADS, of which the legendary Ron Rash (Serena, The World Made Straight) has said good things: "Roads confirms Daren Dean as an important new voice in rural noir." We've also got a good collection coming from Timothy Dodd called MEN IN MIDNIGHT BLOOM that will knock some socks off. In general, I think we've put some of the very best story collections, novels, and creative nonfiction books in the grit lit and indie lit canon over the past few years from the likes of Compton, Drevlow, Dean, Robert Vaughan, Patrick Trotti, Michael Chin, William R. Soldan, Dan Crawley, Amanda Bales, Mark Rogers, Steve Lambert, and Joey R. Poole.

The Workshop Experience

The Famous Author by Lisa Amico Kristel

She sat in the workshop with her twelve pages before her, and she before the five others and The Famous Author too. She wasn’t nervous. She looked forward to the critique. She would use it to improve.

Years later she imagines she must have felt something in the air the minute she entered the room, that she sensed the weight of The Famous Author’s arrogance. Across the years, she can smell it.

But she is projecting a new understanding onto the memory. That day, she was fine.

When it was her turn for critique, she focused on The Famous Author’s hands holding the pages that held her words. What might he say?

The Famous Author shook his head from side to side, and he laughed. He laughed.

Hers was The Famous Author’s last one-hour private session before that evening’s wine and cheese gathering. He was friendly. He asked about her life, topics which were brought up in workshop that related to her piece. A master communicator, he engaged her. She fell into his questions. Doesn’t everyone like to talk about themselves?

Interesting that her protagonist was an insecure young man who had trouble with communication and confrontation. Interesting that she believed she’d overcome her own issues with both. But she realizes now that the method she developed as a child to hide her insecurity—to act like nothing bothered her—had worked against her. It kept her silent when she should have spoken. It made her want to alleviate tension, to make everyone in the room feel comfortable—even the person who made her feel otherwise. The only other person in the room.

As her insecure protagonist would have done, she didn’t direct the conversation to her work. She followed The Famous Author’s whims to other subjects—food, restaurants, raising kids.

His conversation had eaten up fifty minutes of her hour before he asked where she was with her project.

After that day’s workshop, doubt scattered her story in her mind. She stumbled over her thoughts.

“I have several scenes. They’re...not quite linked. I guess it’s…”

“A mess.” He filled in her blank.

She nodded. She sold her writing down the river. Or in this case, into the sea—the Mediterranean was a few hundred meters away.

The Famous Author offered her no other words. No encouragement. No criticism, constructive or otherwise.

He slapped his hands together and stood. “Let’s get to that wine and cheese!” he said.

She answered, “I love cheese.”

He held the door for her.

Clutching her pages, she walked through and felt him following close behind.

She spent the rest of the week being a model workshop participant. Referred to each presenter as the author. Used the pronoun I, never you. Began with what I like about this piece and concluded with what doesn’t work for me. She shared meals, discussions. All the while, a perpetual buzz radiated from her center to her fingertips. It hovered over her keyboard. She was unable to write and not confident she ever would again.

On the last night, she arrived at the gala dinner dressed in blue. She moved about the ballroom making small talk. When she spotted The Famous Author, she decided she ought to be a magnanimous person and thank him.

She wove among tables and groups of chatting teachers and students and approached The Famous Author.

“I’d like to thank you for a constructive week,” she said. Perhaps she said wonderful week, but either way, she lied.

The Famous Author grasped her shoulders, pulled her close, and planted his wet mouth on her lips.

The urge to wipe her lips overwhelmed her, but she didn’t give in, not there in his presence, in the crowded room. She cannot recall if they spoke more, but she is certain she pretended that his behavior was acceptable. She didn’t want to embarrass him.

Back home, she ventured small changes to her text and instantly undid them. She began to avoid writing. Even a glance at her laptop knotted her stomach. Her work was an embarrassment.

At times she wished she could have undone the entire week. Command Z.

Another workshop, two more famous authors. But this pair treated her and her work with respect. First, they saved her, and then she saved herself.

The Famous Author was right. Her writing needed a lot of work. But there are many ways to convey that information, many ways to help a new writer grow. Laughing is not one of them.

She has since edited and revised and improved her manuscript. It no longer brings her shame. She likes it, the way she used to, before The Famous Author ignored its bright spots, focused on its faults, and passed his judgment.

Sometimes, when she imagines her book published, she fantasizes about including The Famous Author in a backhanded acknowledgement. It would read something like this:

And finally, thank you, Famous Author! At the gala affair after your workshop, you sealed your condemnation of this novel with one slobbery and wholly unwanted kiss. For a time, your arrogance suffocated my desire to write. Yet once held up against the generosity of better teachers, your betrayal motivated me to continue, and to prove you wrong.

She knows, however, that these words will not find their way into print. She would never let his name stain her novel’s pages.

Greatest Misses: Writers on Failure

(Un)Dead on Arrival: My Life in Failed Novels By Allison Floyd

Like many writers, I dream of holding a book in my hands, with my name on the cover. I know this isn’t the only metric of “success” (whatever that means), but as a lifelong bibliophile and stereotypical librarian, for me, Writing a Book is The Dream. The problem? I write in the short form (barely). A classic ambivalent Libra, as soon as I seem to be on the road to Writing a Book, I find it’s a cul de sac (fancy French for “dead end”). But I’ve certainly given it the old college try. This is a memorial for my failed novel attempts:

On the Cusp

My first effort, a coming-of-age novel in which the central mystery (if we may call it that) is whether our awkward heroine is a changeling. She makes a friend, who mysteriously disappears. What happened? Who knows? This tale, often set in the woods, was as an excuse to use the word “loam” over and over. I called it good at around 15,000 words, which the astute reader will observe is not novel-length. Also, nothing got resolved (just like life).

Autobiography of a Tick

This sought to be a sendup of the “vampires as romantic antiheroes” trope, experiencing a resurgence at the height of the Twilight Saga’s popularity. It was about a loser who works in the produce section of the grocery store and becomes hopelessly obsessed with a completely nondescript human being: the Beatrice to his Dante, the Mildred to his Philip (Of Human Bondage), the blue light special Bella Swan to his cut-rate Edward Cullen. He lives with two roommates, Leech and Quito (short for mosquito, oh dear), who turn out to be imaginary. He kidnaps his love interest, Darlene, an alarming development, but proves too ineffectual for much to come of it. There’s also a loving antagonist named Apotheosis Smith, the best thing in this trainwreck, but that’s basically saying ol’ Theo is the best house on a bad block. It won a contest for “best first line”. My prize: a critique from some local semi-professional writers, who gleefully ripped it to shreds, citing a lack of plot (guilty) and a preponderance of teenage angst (I was in my 30s). Originally a very padded 50k words (National Novel Writing Month), I reduced it to 10k – 15k words, which amounted to cleaning half of the litterbox.

Appetite

Another attempted Twilight sendup, featuring a doubtful guest, comedic depictions of suburban family life, and psychic vampirism. The psychic vampire was Bernice, and her nemesis, also a psychic vampire, who attempted to wield his power in a benevolent manner, was Javier. Nothing happened for around 50k words (NaNoWriMo again), before I put this out of its misery.

The Woman of the Woods

I was honest about the provenance: “This is my Blair Witch Project”. And it was about as accomplished as the camera angles. I was trying to let the Blair Witch tell her side of the story (I would sympathize with her). In my version, she’s a successful influencer in the food and lifestyle blogosphere, until one day she calls shenanigans and commits a gesture of massive self-sabotage at a photo shoot, involving raw meat, flies, and heavy-handed symbolism (duh). She flees to the woods with her invisible (imaginary?) wolf, Wound Paw, where she deals summarily with a pesky group of would-be documentarians (and the mute sound guy, who may be in cahoots with her).

Like our unwitting documentarians, this project got lost in the woods.

America’s Next Top Vampire

I don’t even like vampires. Blood is gross, and biting isn’t sexy. So why do I keep coming back to them in my failed fiction? If I knew, maybe my fiction would stop failing (and flailing). Anyway, this was a satire of America’s Next Top Model (already a satire of itself), about a bevy of bloodsuckers competing to be—well, you know. I submitted this abortive (and aborted) effort to Tor.com, and the rejecting editor was much kinder than they needed to be: “While there’s an obvious sharp wit in this piece, it ultimately didn’t cohere into a full narrative with fully realized characters.” No kidding. I liked the title and made a half-assed attempt to write something to attach it to. And, yes, the cast and crew went on location to Transylvania.

Bluebeard’s Bel-Air Bachelor Pad

I actually love the crap out of this, a 15,595-word reimagining of VH1’s Rock of Love in which Bluebeard’s victims voraciously compete for his affection. I stand by it (ten years later) and came close to getting it published a couple times. Attention, editors and publishers: let me know if you’re interested!

My Life with Demons and Allison Ford’s Very Important Meeting

These never amounted to more than titles, thank God, the former being another title I thought sounded cool, and the latter to be a misguided attempt at autofiction, drawing heavily from Mrs. Dalloway and Waiting for Godot, probably. Honestly, your guess is as good as mine.

The Clusterfuck Court Chronicles and Other Tales of Suburban Woe: One Librarian's Lament of Downward Mobility

Presently we find ourselves in the throes of a 35,950-word memoir (blissfully vampire-free). It feels like my most coherent attempt, and I hold out hope that I may make it book-length and find a home for it. Because, we writers are a resilient bunch. We have to be, in the face of the failures and rejection, the inner critic, and the stupid jerk who sits on our shoulders and won’t shut up until we attempt this difficult and tedious undertaking, often for no reward other than engaging in the process: getting it down on paper, hoping it might someday matter to someone, holding our book (or the Kindle version) in their hands.

Onward!

What The Hell Am I Thinking?

Writers On Why They Write

For Hope and Freedom

by John Ganshaw

It must be 3 am, I wake up at this time every night, can’t remember if it’s because of the multitude of dreams racing around my head or the cockroaches and their friends using my body as a jungle gym. Everyone else is still asleep, all seventeen others in this cell. I’ll just lay here on the floor and stare up at the ceiling till it's time to take my bucket shower. I still can’t believe I am here. It’s seven months today I have been living this hell, trapped in a Cambodian prison.

The person I came to love did this to me. He was and always will be a beautiful person with a damaged soul. I close my eyes and there he is, just like the first time we met. It’s almost unimaginable what then happened. I had found out about his life as a prostitute, that he had a pimp who had owned him for the last twelve years.

I remember holding him in my arms, with him crying uncontrollably, just repeating, “I am so sorry, I should have told you the truth.”

I could have handled the truth but when he and his “owner” were confronted, it was easier to scheme, lie, and betray than to face their own truth. The pimp managed and controlled the actions of his prostitute, his prey, and his creation—my love. I guess it was inevitable that one of us would need to pay. I paid the ultimate price for trying to save a soul not ready to be saved. His pimp arranged to have me arrested through him, the accusations concocted, false charges filed that led to my arrest.

Innocence means nothing when lies and untruths rule. Tears aren’t going to change this, yet they keep running down my cheeks, a faucet that just can’t be turned off. Two weeks since I went to my bail hearing, and I wonder each day if it was granted. Taking inventory of my body, I have everything I fell asleep with. The bites and open sores on my legs and arms have not disappeared, scabies is still there, and the itching is still there. Yup, nothing was miraculously cured during the night. I might as well get up, careful not to hit my head on that fucking ceiling fan. The one that attacked me two days ago, causing a river of blood to run down my forehead and face. Don’t need to relive that again.

Since the fainting spell last week, I am allowed to go outside and sit on the concrete steps. The perimeter is surrounded by yellow caution tape, a safety measure since we are in a Covid quarantine block. Sharing my quarantine with seventeen others in the same cell. The sun is quickly rising, and soon I can go outside, like a dog into the fenced yard. We will hear the key turn, the door opens ever so slightly, and Buntha will grab me, and we will be out in the fenced-in open air. It’s so much easier to write freely when not sitting in a dark and dank cell. I’ve been writing every day for the last seven months, journal entries, letters to friends, to God, to anyone I could think of. Without this experience, I’m not sure I would have had the fortitude to even start such a venture. I wonder if I should thank him, the person responsible for where I am, for such a wonderful opportunity. My writings will always be a reminder that this wasn’t a dream but living proof of the reality of injustice.